Principle 4: Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics)

To build and maintain our own stores, shops and other businesses and to profit from them together.

Kwanzaa: Day Four

Kwanzaa: Day Three

Kwanzaa: Day Two

Kwanzaa: Day One

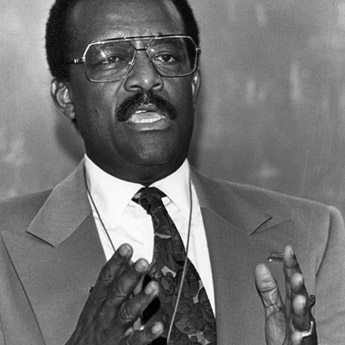

What Johnnie Cochran Said About Police Officers In His Autobiography

“The policeman on the street is the most powerful person in the criminal justice system. If he is in the grip of some grim private impulse or carries with him some bigoted private agenda, he can- all on his own- take your life, beat you and choose to lie about your guilt or innocence. If the rest of the system the elects to accept his word without question, you are utterly at his mercy.” -From, “Journey to Justice” By: Johnnie Cochran

“The policeman on the street is the most powerful person in the criminal justice system. If he is in the grip of some grim private impulse or carries with him some bigoted private agenda, he can- all on his own- take your life, beat you and choose to lie about your guilt or innocence. If the rest of the system the elects to accept his word without question, you are utterly at his mercy.” -From, “Journey to Justice” By: Johnnie Cochran

Black History Fact Of The Day

Quote Of The Day

“‘Bloom where you’re planted, child,’ she used to say whenever I talked about all the things I was going to do when I got back home, back to the city, where we had all kinds of things- stores, TVs, indoor plumbing- that she didn’t have in the country. ‘Do what you can, with what you have, where you are.'” -Patti LaBelle

Book Excerpt Of The Week- Part 3: “Amusing Ourselves To Death” By: Neil Postman

“…Americans are the best entertained and quite likely the least well-informed people in the Western world. I say this in the face of the popular conceit that television, as a window to the world, has made Americans exceedingly well informed. Much depends here, of course, on what is meant by being informed. I will pass over the now tiresome polls that tell us that, at any given moment, 70 percent of our citizens do not know who is the Secretary of State or the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Let us consider, instead, the case of Iran during the drama that was called the ‘Iranian Hostage Crisis.’ I don’t suppose there has been a story in years that received more continuous attention from television. We may assume, then, that Americans know most of what there is to know about this unhappy event. And now, I put these questions to you: Would it be an exaggeration to say that not one American in a hundred knows what language the Iranians speak? Or what the word ‘Ayatollah’ means or implies? Or knows any details of the tenets of Iranian religious beliefs? Or the main outlines of their political history? Or knows who the Shah was, and where he came from?

“…Americans are the best entertained and quite likely the least well-informed people in the Western world. I say this in the face of the popular conceit that television, as a window to the world, has made Americans exceedingly well informed. Much depends here, of course, on what is meant by being informed. I will pass over the now tiresome polls that tell us that, at any given moment, 70 percent of our citizens do not know who is the Secretary of State or the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Let us consider, instead, the case of Iran during the drama that was called the ‘Iranian Hostage Crisis.’ I don’t suppose there has been a story in years that received more continuous attention from television. We may assume, then, that Americans know most of what there is to know about this unhappy event. And now, I put these questions to you: Would it be an exaggeration to say that not one American in a hundred knows what language the Iranians speak? Or what the word ‘Ayatollah’ means or implies? Or knows any details of the tenets of Iranian religious beliefs? Or the main outlines of their political history? Or knows who the Shah was, and where he came from?

Nonetheless, everyone had an opinion about this event, for in America everyone is entitled to an opinion, and it is certainly useful to have a few when a pollster shows up. But these are opinions of a quite different order from eighteenth- or nineteenth-century opinions. It is probably more accurate to call them emotions rather than opinions, which would account for the fact that they change from week to week, as the pollsters tell us. What is happening here is that television is altering the meaning of ‘being informed’ by creating a species of information that might properly be called disinformation. I am using this word almost in the precise sense in which it is used by spies in the CIA or KGB. Disinformation does not mean false information. It means misleading information- misplaced, irrelevant, fragmented or superficial information- information that creates the illusion of knowing something but which in fact leads one away from knowing. In saying this, I do not mean to imply that television news deliberately aims to deprive Americans of a coherent, contextual understanding of the world. I mean to say that when news is packaged as entertainment, that is the inevitable result. And in saying that the television news show entertains but does not inform, I am saying something far more serious than that we are being deprived of authentic information. I am saying we are losing our sense of what it means to be well informed. Ignorance is always correctable. But what shall we do if we take ignorance to be knowledge?” -From, “Amusing Ourselves To Death: Public Discourse In The Age Of Show Business” By: Neil Postman

[SIDEBAR: I happen to think that the news is a lot more “deliberate” than the author expressed…A thought provoking book though.”]

Book Excerpt Of The Week- Part 2: “Amusing Ourselves To Death” By: Neil Postman

“You may get a sense of what is meant by context-free information by asking yourself the following question: How often does it occur that information provided you on morning radio or television, or in the morning newspaper, causes you to alter your plans for the day, or to take some action you would not otherwise have taken, or provides insight into some problem you are required to solve? For most of us, news of the weather will sometimes have such consequences; for investors, news of the stock market; perhaps an occasional story about crime will do it, if by chance the crime occurred near where you live or involved someone you know. But most of our daily news is inert, consisting of information that gives us something to talk about but cannot lead to any meaningful action. The fact is the principal legacy of the telegraph: By generating an abundance of irrelevant information, it dramatically altered what may be called the ‘information-action ratio.’

“You may get a sense of what is meant by context-free information by asking yourself the following question: How often does it occur that information provided you on morning radio or television, or in the morning newspaper, causes you to alter your plans for the day, or to take some action you would not otherwise have taken, or provides insight into some problem you are required to solve? For most of us, news of the weather will sometimes have such consequences; for investors, news of the stock market; perhaps an occasional story about crime will do it, if by chance the crime occurred near where you live or involved someone you know. But most of our daily news is inert, consisting of information that gives us something to talk about but cannot lead to any meaningful action. The fact is the principal legacy of the telegraph: By generating an abundance of irrelevant information, it dramatically altered what may be called the ‘information-action ratio.’

In both oral and typographic cultures, information derives its importance from the possibilities of action. Of course, in any communication environment, input (what one is informed about) always exceeds output (the possibilities of action based on information). But the situation created by telegraphy, and then exacerbated by later technologies, made the relationship between information and action both abstract and remote. For the first time in human history, people were faced with the problem of information glut, which means that simultaneously they were faced with the problem of a diminished social and political potency.” -From, “Amusing Ourselves To Death: Public Discourse In The Age Of Show Business” By: Neil Postman

Book Excerpt Of The Week- Part 1: “Amusing Ourselves To Death” By: Neil Postman

“To Understand the role that the printed word played in providing an earlier America with its assumptions about intelligence, truth and the nature of discourse, one must keep in view that the act of reading in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had an entirely different quality to it than the act of reading does today. For one thing, as I have said, the printed word had a monopoly on both attention and intellect, there being no other means, besides the oral tradition, to have access to public knowledge. Public figures were known largely by their written words, for example, not by their looks or even their oratory. It is quite likely that most of the first fifteen presidents of the United States would not have been recognized had they passed the average citizen in the street. This would have been the case as well of the great lawyers, ministers and scientists of that era. To think about those men was to think about what they had written, to judge them by their public positions, their arguments, their knowledge as codified in the printed word. You may get some sense of how we are separated from this kind of consciousness by thinking about any of our recent presidents: or even preachers, lawyers and scientists who are or who have recently been public figures. Think of Richard Nixon or Jimmy Carter or Billy Graham, or even Albert Einstein, and what will come to your mind is an image, a picture of a face, most likely a face on a television screen (in Einstein’s case, a photograph of a face). Of words, almost nothing will come to mind. This is the difference between thinking in a word-centered culture and thinking in an image-centered culture.” -From, “Amusing Ourselves To Death: Public Discourse In The Age Of Show Business” By: Neil Postman

“To Understand the role that the printed word played in providing an earlier America with its assumptions about intelligence, truth and the nature of discourse, one must keep in view that the act of reading in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had an entirely different quality to it than the act of reading does today. For one thing, as I have said, the printed word had a monopoly on both attention and intellect, there being no other means, besides the oral tradition, to have access to public knowledge. Public figures were known largely by their written words, for example, not by their looks or even their oratory. It is quite likely that most of the first fifteen presidents of the United States would not have been recognized had they passed the average citizen in the street. This would have been the case as well of the great lawyers, ministers and scientists of that era. To think about those men was to think about what they had written, to judge them by their public positions, their arguments, their knowledge as codified in the printed word. You may get some sense of how we are separated from this kind of consciousness by thinking about any of our recent presidents: or even preachers, lawyers and scientists who are or who have recently been public figures. Think of Richard Nixon or Jimmy Carter or Billy Graham, or even Albert Einstein, and what will come to your mind is an image, a picture of a face, most likely a face on a television screen (in Einstein’s case, a photograph of a face). Of words, almost nothing will come to mind. This is the difference between thinking in a word-centered culture and thinking in an image-centered culture.” -From, “Amusing Ourselves To Death: Public Discourse In The Age Of Show Business” By: Neil Postman